GTK: Unsustainable economics of the oil industry a threat to the global economy

11 February 2020

The Geological Survey of Finland (Geologian tutkimuskeskus, GTK) released a report titled Oil from a Critical Raw Material Perspective, warning that the increasingly unsustainable economics of the oil industry may lead to a major disturbance in the global financial system and energy markets.

The GTK, which operates under the government’s Ministry of Economic Affairs, is the European Commission’s lead coordinator of the EU’s ProMine project, its flagship mineral resources database and modeling system. The ~500 pages report, written by GTK senior scientist Simon Michaux and dated 22 December 2019, was produced as an internal research exercise for the Finnish government.

Today, approximately 90% of the supply chain of all industrially manufactured products depend on the availability of oil derived products or services, and oil demand is still growing by ~1 million barrels per day (mbd) every year. While the oil market is currently oversupplied, 81% of existing world liquids production is already in decline, notes the report. Peak oil discovery was in 1962—since then rate of resource discovery has been declining persistently.

In January 2005, Saudi Arabia increased its number of operating rig count by 144%, to increase oil production by only 6.5%. This suggests that the market swing producer (as Saudi Arabia was seen) was not able increase production enough to meet increasing demand. Global conventional crude oil plateaued in 2005. This would prove to be a decisive turning point for the industrial ecosystem. Since then, unconventional oil sources like tight oil (LTO) produced from shale formations through fracking, and oil sands have made up the demand shortfall. Since 2005, US tight oil contributed 71.4% of new global oil supply. In 2018, the US tight oil sector accounted for 98% of the global oil production growth.

Meanwhile, starting in January 2005, the prices of oil and other commodities—base metals, precious metals, gas and coal—blew out in an unprecedented bubble. The second worst economic correction in history, the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008, was not enough to resolve the underlying fundamental issues. After the GFC, the volatility in commodity price continued. The report makes the case that the GFC was created as the entire industrial ecosystem was put under unprecedented stress, where the weakest link broke. That weakest link was in the financial markets. The strain that created this unprecedented stress was triggered by the global oil production plateauing. If further analysis supports this hypothesis—the report says—then the GFC was created by a chain reaction that had its origins in the oil market.

While Saudi Arabia may no longer be able to ramp up production very much, the US shale oil sector could be on the brink of unraveling due to massive unrepayable debt and declining production rates. The average production of a fracked well increased by 28% between 2010 and 2018, but water injection increased by 118% over the same period—indicating a significant increase in fracking costs. The productivity (per rig as measured by the EIA) of the US tight oil sector in 2018 was lower than in 2016. This suggests that the US tight oil sector is approaching its peak production. Most oil producers in the US tight oil fracked sector have a negative cash flow and struggle to raise capital to develop upstream infrastructure. This is unfortunate, as to maintain production levels, ongoing new drilling is required which requires capital.

The report concludes that the US shale oil production is approaching its terminal decline, which is likely to occur within the next 5-10 years, with the possibility that it has already peaked due to contraction of upstream capital investment. The projections of peak oil around 2040 by the IEA or the US EIA are highly unlikely.

Oil is a finite natural non-renewable resource and the planet Earth is a finite system. At some point, rates of resource discovery and oil extraction rates will peak and decline. However, the traditional peak oil theorists were overly focused on the geological decline of oil fields, and neglected to consider economic factors—such as the quantitative easing (QE) by central banks after the GFC and the near-zero interest rate policy that enabled the shale oil “miracle”.

Oil will peak in production not because there is not enough reserves in the ground to meet demand, but because consumers cannot support the oil price at a level that allows oil producers to remain economically viable. Although there is still plenty of oil in the ground, most of new oil resources—LTO, oil sands or deepwater resources—are increasingly expensive to access and require a massive amount of investment.

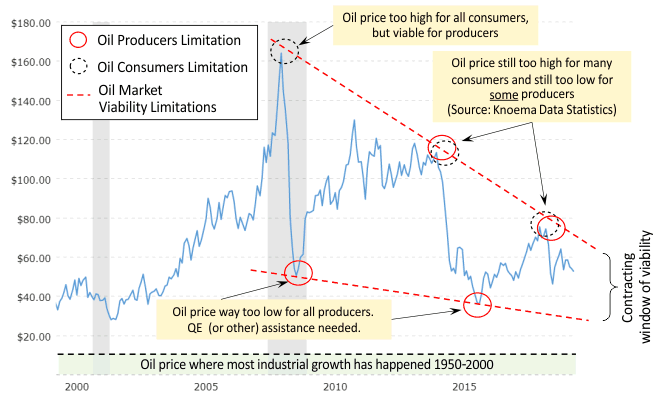

Peak oil will be driven by a combination of a window of viability between an oil price low enough for consumers to support where economic growth is possible, and an oil price high enough for producers to be economically viable. It is not clear when peak oil production will happen, but it is clear that the viable window of oil market operation is closing, Figure 1. The current economic system cannot sustain oil prices above $100 a barrel and keep growing, while producers for most new fields cannot sustain profits at prices as low as $45 a barrel without more borrowing.

(Source: GTK)

Levels of global debt are now thoroughly out of control, the report says. The US government debt creation has been approximately twice the rate of economic growth over the last 40 years. By increasing the volume of debt, countries were able to maintain growth as costs of energy went up. As a result, most national economies now have debt to GDP ratio exceeding 90%, which means that they need to go further into debt just to keep their economies functioning while maintaining debt repayments.

The assumption that alternative mobility technologies—electric vehicles (EV) or hydrogen fueled vehicles—will replace internal combustion engines (ICE) and reduce the global oil consumption is unlikely to work as planned, the report concludes. An analysis of the logistical practicalities of such transformation and of the extra capacity required in the electrical power grids to charge the necessary number of batteries shows that the task to transform the existing fleet of ICE vehicles into EVs and manage their operation is a far larger challenge than currently understood. Another study is being planned to examine the volume quantity of minerals needed to manufacture the required batteries, solar panels and wind turbines to support a fully renewable power system that supports a fully EV fleet of vehicles. Preliminary results suggest that global mineral reserves of cobalt, nickel, lithium, and neodymium are not large enough to supply raw materials for this task. Finally, even if possible, it may be already too late for an orderly planned transition—it would probably take 20-30 years to phase oil systems out and substitute a replacement system, while oil production may peak sometime in the next few years.

In its concluding sections, the report provides a number of recommendations. These include:

- Technical professionals and policymakers should focus on the creation of a high technology society, based on a smaller clean energy footprint that is not reliant on endless material growth. If this is not achieved, the alternative is the degradation (and fragmentation) of the current industrial ecosystem.

- A new systems study should be conducted of the global industrial ecosystem, repeating the 1972 Limits to Growth systems analysis with up-to-date information and more inputs.

- Europe is currently heavily dependent on energy resources that are extracted from the ground. This state of affairs is likely to continue for decades, even with the penetration of the electric vehicle technology into the market place. It is recommended that oil, gas, coal and uranium are all added to the European Critical Raw Material (CRM) list.

Source: GTK: Oil from a Critical Raw Material Perspective | Nafeez Ahmed on Vice